Ezra Ngala, an casual development employee, is having difficulties to make finishes satisfy in a slum in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi. “I am seeking to survive,” he states though describing that he can not feed his wife and four-12 months-aged son.

“For the previous handful of months there has been a surge of men and women like myself going hungry. The authorities states that the war in Ukraine is the cause of all this.”

Steep rises in worldwide food stuff and gasoline selling prices considering that the Russian invasion of Ukraine have remaining thousands and thousands more Africans struggling with hunger and meals insecurity this calendar year, the UN, neighborhood politicians and charities have warned. The cost rises have compounded economic issues triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, sparking problems of unrest in the hardest-strike nations around the world. Swaths of Africa confront an “unprecedented food emergency” this 12 months, in aspect simply because of the war in Ukraine, the Entire world Foods Programme has claimed.

“The conflict in Ukraine [sparked a] worldwide rate hike of gas, fertilisers and also edible oil and sugar and wheat significantly. This is bringing sizeable shocks to the program,” Ahmed Shide, Ethiopia’s finance minister informed the Monetary Periods.

In an place stretching from northern Kenya to Somalia and substantial pieces of Ethiopia, up to 20mn men and women could go hungry in 2022, the UN’s Food stuff & Agriculture Corporation has claimed, owing to the worst drought in 4 decades, exacerbated by the fallout from the war in Ukraine. Much more than 40mn men and women in the Sahel and west Africa this calendar year confront acute food stuff insecurity, in accordance to the FAO, up from 10.8mn men and women 3 several years ago.

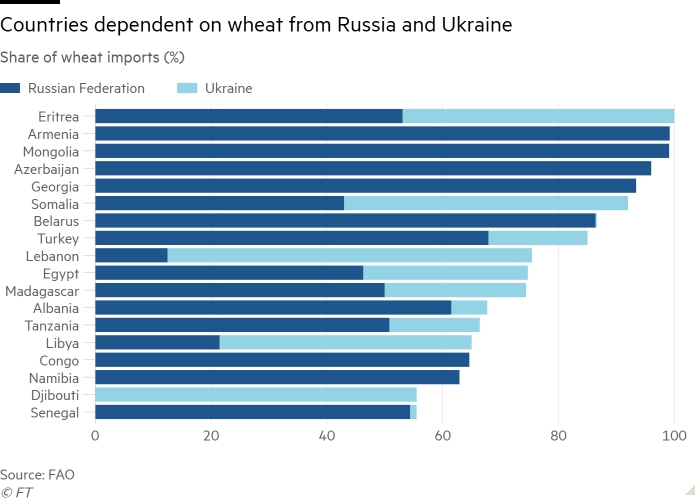

Before the war, Russia and Ukraine accounted for a double-digit share of wheat imports in extra than 20 sub-Saharan African nations, together with Madagascar, Cameroon, Uganda and Nigeria, in accordance to the FAO. Eritrea relies on these two nations around the world for all of its wheat imports.

Even individuals nations around the world not reliant on imports from Russia and Ukraine have been hit by growing price ranges.

Responding to the development, the Planet Financial institution on Wednesday mentioned it experienced authorized a $2.3bn programme to assistance international locations in japanese and southern Africa deal with food insecurity.

The IMF forecasts that buyer charges in sub-Saharan Africa will top 12.2 for each cent this year — the best in pretty much two decades. In Ethiopia, foodstuff selling prices rose 42.9 for every cent in April on the exact same month a year earlier.

There are fears that higher food price ranges could gasoline unrest in poorer nations, where food counts for a better part of everyday investing than in developed nations around the world.

During the 2007-08 foods disaster, which was triggered by a spike in vitality costs and droughts in crop-creating locations, about 40 countries faced social unrest. A lot more than a third of all those countries had been on the African continent.

Even ahead of the Russian invasion in late February, the pandemic had now strike financial advancement on the continent. “Africa was previously battling with foodstuff insecurity,” claimed Wandile Sihlobo, chief economist at the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa. “These African nations around the world experienced diminished potential to cushion their populace from food stuff price tag fluctuations.”

There have previously been some indicators of unrest. Landlocked Chad declared a food items “emergency” previously this thirty day period. In Uganda, 6 activists ended up arrested for protesting towards better meals prices at the end of May possibly, according to Amnesty Intercontinental. The soaring charge of foods has due to the fact May perhaps spurred avenue protests in Nairobi underneath the hashtags #LowerFoodPrices and #Njaa-Revolution — which means “hunger” revolution in Swahili.

“People are hungry, the reality is that people can’t pay for to continue to keep up with these soaring rates. You wake up each and every day, and selling prices are soaring,” stated Lewis Maghanga, a regional campaigner on the expense of residing.

Jackline Mueni, who bakes cakes for weddings and birthdays in Nairobi, is experience the pinch. “Things are just acquiring undesirable,” she claimed, including that in the three many years she had been in small business this was by much the worst time. “In the last a few months, foods selling prices have actually rocketed.”

In Could, the value of edible oils jumped a lot more than 45 for every cent from a 12 months in the past in Kenya, when flour enhanced 28 for each cent, in accordance to the Planet Lender. “This is the worst time at any time. I was incredibly comfortably earning money, recovering charges and creating a financial gain. I was providing an regular of 5 cakes a working day. Now, one or two, if I am lucky,” claimed Mueni.

Even Nigeria, an oil producer and a member of Opec, has been hit by global food items and gasoline price ranges. Africa’s most populous state exports crude oil but depends on fuel imports. It is also a massive foods importer, especially of grains. The price tag of bread in Lagos has risen from 300 naira ($.72) before the pandemic to 700 naira this year, according to Chibundu Emeka Onyenacho, analyst at emerging marketplaces financial institution Renaissance Funds.

“If you have all of a sudden moved to 700 [naira for a loaf of sliced bread], that is placing strain on anybody that is currently being compensated the [monthly] minimum wage of 30,000 naira,” claimed Onyenacho.

He additional that the rate of wheat flour intended that in rural spots, folks blended it with flour created from cassava, a low-cost root vegetable, for the reason that they were being “willing to compromise” on good quality to reduce the expense of merchandise eaten every day, these kinds of as bread.

Back in Kenya, soaring gasoline selling prices suggest development worker Ngala spends around fifty percent his income on gas costs. As a end result, some dishes have turn out to be unaffordable.

“We simply cannot afford to pay for fundamental issues like cooking oil and maize flour,” he explained, the latter to make local staple ugali, a cooked maize-flour dough. “There are individuals who can’t find the money for even one food a day.”